“Ultimately, my operation saved my life”

For student Izzy Scott, the road to her CTEPH diagnosis was long and frustrating.

“I spent a year going back and forth to my GP because of breathlessness that kept getting worse. I was out of breath walking across my university campus, and I would have a tight chest that was painful too. I just couldn’t get oxygen in.

I was diagnosed with asthma, so I went through all the inhalers, and all this time I was getting more and more breathless. People started to notice how often I had to stop, even walking on flat surfaces.

I was then told by my GP that it wasn’t asthma, but that it was all in my head – and it was anxiety and stress causing my breathlessness.

I caried on with things as best as I could. But my lips started going blue after I climbed the stairs, I started getting palpitations, and it got the point where I couldn’t even put my socks on. Even standing up and cooking would exhaust me.

It was frightening knowing there was something wrong but not knowing what it was. I was getting worse, but had no idea why, and my GP didn’t seem concerned.

In December last year I went to visit my parents and they saw how exhausted I was just going to the toilet, so they insisted I saw an out-of-hours GP there and then.

A blood test showed I had clots and a chest x-ray showed my heart was enlarged. I was admitted to my local hospital and then transferred to a specialist centre where I was diagnosed with CTEPH.

I had never heard of it before. On the one hand it felt like a weight had been lifted to finally have a diagnosis, and confirmation that it wasn’t all in my head. But on the other hand, it was scary.

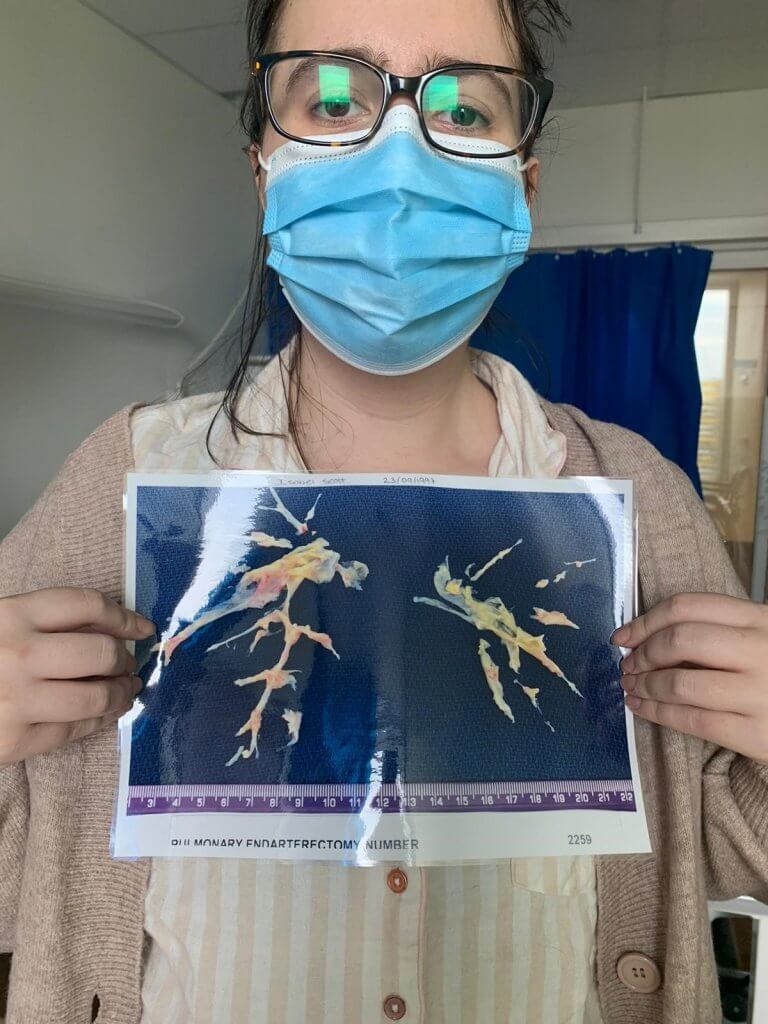

The option of a pulmonary endarterectomy (operation to remove the clots) was discussed, and I was told it was major surgery, but that it would give me a chance of a ‘normal’ life. I had no reservations, as I didn’t want to spend my life feeling breathless.

I was in hospital for three weeks before being discharged for Christmas and managed to carry on studying before my surgery in August this year.

I had time to come to terms with what would happen during the operation but because of COVID-19 visiting restrictions, I was totally alone.

I was on my own in the hospital for three days before the surgery and it was really hard thinking that if I didn’t wake up, the last conversation with my family would have been via Face Time.

The surgery went well but I stayed in hospital for three weeks afterwards because I had a brain bleed. I cried when I went outside for the first time to breathe the fresh air and feel the sun.

Recovery has gone well and it’s insane how much better I can breathe now.

I want to raise awareness of CTEPH because I had no idea of what it was before it happened to me and young people especially are not always aware of what could happen. It’s a complicated condition to explain to people.

I am always wondering how different things may have been if it had been detected earlier. Would it have got to the point of needing surgery?

I went through a year of going back and forth with my GP and even after diagnosis I still encounter medical professionals who don’t know what it is. I understand it’s rare, but it can kill people. Ultimately, my operation saved my life.”