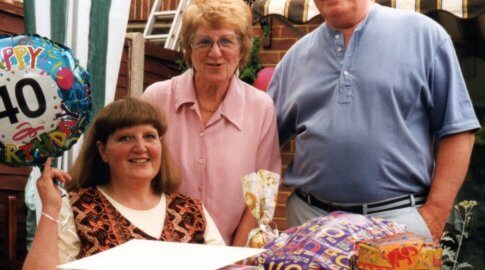

“It’s not a life without problems, but nobody’s life is perfect”

In an honest account of her transplant journey, 43-year-old Tamworth racehorse trainer Kirsty Smith shares the story of her new lungs.

“I was living in Northumberland when I was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension back in January 2001. I’d started to get breathless and black out, and went through various tests with different doctors until finally, a right heart catheter at the Freeman Hospital in Newcastle showed what was wrong. I was sent up to the PH ward where I would visit for the next 15 years.

I’d gone from never being ill, riding horses and working non-stop, to bang, being struck down with this. I’m quite a resilient person, but at that point, the whole world just caved in. It was a horrible time.

After an operation to reduce the pressures in my heart, I was told I could start treatment. I vividly remember a nurse coming to my bed with a huge nebuliser, and putting this big box down next to me. I was told I would have to nebulise the drug every three hours, and I asked her to take it away.

I refused to have anything to do with the nebuliser, so I was given a Hickman line, which stayed in for 15 years. I was told I’d never ride again, but I did. I was told I wouldn’t ski again, but I did. I stopped competing, but I still rode racehorses.

The first time I was listed for transplant was in 2013. I’d broken my leg badly in a riding accident and ended up having a nerve block while it was bashed around, pinned and plated – whilst I was awake. My heart couldn’t cope with the trauma, so I was assessed and put on the list.

I didn’t know it at the time, but no-one thought I would survive the weekend. Then, all of a sudden, two days later, I was fine and came off the transplant list. I don’t know what it is inside me that just keeps on going.

Two years later, I started going downhill quickly and went back onto the transplant list in January 2015. I had a suitcase packed and ready for when the call would come, as I never knew when it would be.

I was scared I wasn’t going to get a transplant in time, but the call came four months later, on May 10th

That morning I’d been over to a Point to Point race at Melton Mowbray, and it was mayhem. I remember leading one of the horses back from the winner’s enclosure and I couldn’t breathe.

I was living by myself at this point and at the end of the day I decided to go straight home to bed as I was so tired. I don’t know what it was but even though I was exhausted I decided have a bath and wash my hair – it was like I knew what was coming.

My head hit the pillow at 10pm and the phone rang. I was told that lungs had been found and a car would be with me in an hour. I called my mum and we were taken to East Midlands Airport where I was put straight on a private jet up to Newcastle. It was all very surreal.

During that flight I kept telling mum not to get too excited as sometimes the organs aren’t right, or you’re not right, and I’d heard so many stories of people being disappointed. I didn’t want to get my hopes up.

I had the transplant at 7am, nine hours after receiving the call at home. Within a couple of days of having the operation I looked totally different. Everything was pink and white again because my body was now getting oxygen. It was incredible. It was literally a transformation – as if overnight, my body had healed.

I thought I couldn’t breathe because I’d spent 15 years struggling to breathe, and now I could breathe normally, but it felt wrong because I wasn’t used to it. Mentally, it felt alien.

Although I looked better, the first 48 hours after the operation were difficult. I thought I couldn’t breathe because I’d spent 15 years struggling to breathe, and now I could breathe normally, but it felt wrong because I wasn’t used to it. Mentally, it felt alien.

I freaked out and kept panicking. I also couldn’t talk properly because my vocal chords had been damaged during the operation and I kept vomiting because of the anaesthetic. It was all just madness. Being honest, at that point, I was wishing I hadn’t gone ahead with it all.

Soon though, everything calmed down and I got used to breathing normally. My voice came back and I left intensive care after 24 hours. My hair fell out – probably because of the trauma – but it did come back, although now it’s curly!

I was put on anti-rejection drugs straight away and I will take them for life. I get a few side effects – mostly shakiness and achiness – but they affect everyone differently.

After a while, my lung function began declining and my body started rejecting the lungs, so I had intense radiotherapy. It made me lose a lot of weight, but it didn’t really do anything. I think that like PH therapies, the treatments are so individual – they work differently for different people.

I am now having some new treatment, extracorporeal photopheresis, for chronic rejection and to try and keep my lungs at their current level. The decline doesn’t happen with everybody, and it’s something I don’t think is fully understood yet.

I think of my donor often. There’s a family out there grieving, while I’m living a life, but I hope they find some sort of solace in that she helped so many people.

Although my lung function has gone down, I do function quite well. I’m not going to run a marathon, but I can sit on a horse and go up and down the gallops, ride dressage tests and be absolutely fine.

The lady who donated her lungs to me saved five people’s lives with her organs. All I know is that she was 50, and that I probably wouldn’t have made another month or two without her. After about six months I wrote to her family, via the hospital. I wrote the letter on the beach in Devon after I’d been kayaking. I never heard back, but I didn’t mind – I just wanted them to know what she had done for me.

I think of my donor often. There’s a family out there grieving, while I’m living a life, but I hope they find some sort of solace in that she helped so many people.

Three years on, yes, I’ve had ups and downs, but they are irrelevant. I’ve trained racehorses, I’ve lived a life, I’ve got a family – and I wouldn’t have been able to without this. It’s not a life without problems, but nobody’s life is perfect.

Having a transplant for me has been wonderful as it’s meant I can look forward again. I can plan things, whereas before I was just waiting – for the worst to happen, or for a transplant that would give me these years. It doesn’t matter how many years you get really, as long as you’ve made the most of them.

Without the transplant I wouldn’t be here now. I wouldn’t be winning races with the horses, or seeing my nieces and nephews grow up. It means everything.

Why we need to talk about organ donation

Donating organs is selfless and I’m really grateful to my donor’s family too, for respecting her decision. I think anyone who goes on the register is amazing, but the part the family play is vital too and people need to understand the importance of talking about their wishes. No-one wants to talk about death, but we need to have those conversations.

My transplant has inspired a huge number of my friends and family to sign the organ donation register, but it still took a lot of time for some to do it, even though it takes less than five minutes. It’s easy for people to forget or put it off, and that’s a shame.

If you needed a new heart or lungs, would you accept a donation yourself? If you would, you need to sign the register. Anyone could need a new organ, at any point. I never expected to need new lungs, but you don’t know what’s going to happen in the future.”